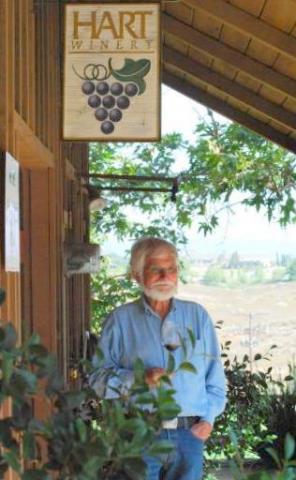

As an earlier pioneer of the Temecula Valley, outside of San Diego, Joe Hart, only the fourth person to start a winery in the area, has spent the better part of 30 years as a champion for the Temecula wine region. Sequestered in one of Southern California’s last “unknown” wine regions Hart Winery capitalizes on the soils and climate at 1,500 feet above sea level to produce the premium varietals like Merlot, Fume´ Blanc, Viognier, Grenache Rose´, Syrah, Sangiovese, Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. The renaissance of the California wine industry in the 1970s found Joe Hart and Nancy Hart and their three sons planting their first vineyards in 1973.

As an earlier pioneer of the Temecula Valley, outside of San Diego, Joe Hart, only the fourth person to start a winery in the area, has spent the better part of 30 years as a champion for the Temecula wine region. Sequestered in one of Southern California’s last “unknown” wine regions Hart Winery capitalizes on the soils and climate at 1,500 feet above sea level to produce the premium varietals like Merlot, Fume´ Blanc, Viognier, Grenache Rose´, Syrah, Sangiovese, Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. The renaissance of the California wine industry in the 1970s found Joe Hart and Nancy Hart and their three sons planting their first vineyards in 1973.

Your first experience with wine was in Germany, which got you started. Describe that experience with those wines and how those eventually lead you to forming your own winery.

There were two wine experiences in fairly quick succession, the first in Germany, followed soon after by one in Italy. Shortly after graduating from San Diego State I had been a reluctant draftee into the US Army, and after completing basic and advanced infantry training at Fort Ord I was sent to Germany, where I ended up in Augsburg, Germany, at a relatively cushy desk job in the Quartermaster Corps.

Several of my Army buddies and I signed up for an Enlisted Men’s Club bus tour to the Bodensee and the island of Mainau, on the German-Swiss border. After an entertaining, gorgeous summer day that included a couple of boat rides, rose gardens, lunch on the island that ended with a dish of ice cream topped by a miniature paper parasol, we boarded the bus for our return trip to Augsburg. Somewhere in the rolling, pine-forested hills of Bavaria we stopped at a typically picturesque gasthaus for dinner. The dinner was classic for the region - a sausage plate with sauerkraut and potatoes - and a bottle of white wine on each table. Overcoming my teetotaling scruples, I tried the wine. It was delicious, and the perfect complement to the simple meal. The wine was, I am sure, just a fresh, simple, local one of modest pedigree, but in that setting, with that meal, it was a perfect wine!

A few months later, in December, a buddy and I took a twelve-day train trip to Italy, traveling in third-class rail cars (some with wooden seats). After crossing the Alps our first Italian destination was Venice. Arriving late afternoon on a gloomy, overcast, damp day, and after finding a hotel room, we set out to explore the city. We stopped at a modest, canal-side trattoria for dinner. Again, as in Bavaria, there was a bottle of wine on the table, but this time it was red. So, once again, I tried the wine. The entree was, in memory, a modest, basic red-sauced pasta, again perfectly complemented by the dry, simple, and doubtlessly local, wine. Once again, a perfect wine!

After completing my military obligation, I returned to San Diego State for two graduate years in pursuit of a secondary teaching credential, married while a student, and taught junior high for several years in Fullerton, California. No wine, however; the beverage at our wedding was Laura’s Fruit Punch. Pretty dismal, in retrospect!

One day I walked into our local neighborhood wine shop, randomly perused the shelves, and bought a 375 ml. bottle of Charles Krug dry red Zinfandel. Taking the bottle home, I asked my wife if she would like to try the wine with dinner, she was agreeable, and we liked it! Another perfect wine!

From there, we began to explore wine, go to wine tastings, visit wineries, and drink wine regularly with meals, and eventually I took a basic UC Davis Extension wine course, “Winemaking, At Home and Beyond”, taught by professional winemakers who had begun their careers as amateur home winemakers, including, among others, Joseph Swan and Cary Gott. They invited the class attendees to visit them at their wineries, and, probably to their great surprise, we did (and had some memorable experiences!).

You planted your vines in the Temecula Valley in the 1970s. What about the region caused you to believe that Temecula could produce excellent wines?

The first couple of years after returning to teaching, in Carlsbad, I commuted daily from San Diego to Carlsbad. At some point, I discovered a Brookside Winery tasting room in Escondido, so most Fridays I swung over to Escondido to taste and buy the wines for the week. Brookside was an old Guasti/Cucamonga winery with a dozen or so satellite tasting and wine sales rooms scattered about Southern California, with their production facilities in the Cucamonga area. Because of the encroachment of housing and industrial development it was becoming increasingly difficult to continue farming wine grapes in Cucamonga, so they had purchased several hundred acres in Temecula. In 1968 Brookside planted extensive vineyards on their newly acquired property - several hundred acres - from which they began producing wine in, I’m guessing, 1971, trucking the grapes from Temecula to Cucamonga in open trucks, trailing juice all the way! The wines, made in Cucamonga from Temecula-grown grapes, were bottled under Brookside’s premium label, Assumption Abbey, and I first tasted them on my Friday Brookside tasting room commute. While not great, they seemed well made, showing considerable promise in a North Coast sort of way. We had considered moving North, and even looked at Russian River property (growing prunes, at the time), but really couldn’t give up two teaching jobs (my wife was teaching kindergarten in Carlsbad) and we didn’t have the financial resources to make the move anyway. But Temecula was only forty miles away, and Nancy could continue teaching while we bought property, planted vineyard, and started a small, boot-strap sort of winery. So that’s what we did, purchasing ten acres of raw land in 1973!

Do you feel that Temecula can ever rival other, better known wine regions in California?

Temecula can rival other areas if we grow the right grape varietals, ones well-suited to our soils and climate, follow the very best viticultural practices in our vineyards, and practice exemplary winemaking in our cellars. Simple, no? One issue we face is arriving at some sort of consensus on which grape varieties we should focus on; some maintaining that we can grow virtually any grape we want to, but others of us - me, for example - who continue to persevere in the search for the grape(s) that will help in defining a regional identity.

Describe the soil types in Temecula and what varieties you think show best.

Most of our soils are granitic in nature with some clay content, with some volcanic soil overlay from ancient volcanic activity in the coastal range on the west side, where the coastal influence is most pronounced. Our elevations range from 1200 feet to 2500 feet in elevation. My personal opinion, one not shared by all of my Temecula colleagues, is that Mediterranean varieties do best here, including Tempranillo, Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Viognier, Sangiovese, and Barbera, for starters, with lots of room for experimentation with less well known Spanish and Italian varietals. Bordeaux varieties that do well here are, again in my opinion (and experience), Sauvignon Blanc and Cabernet Franc; Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon are more challenging. Riesling and Gewurztraminer have both been grown successfully, Chardonnay produces decent wines, and Pinot Noir is a definite non-starter.

As a boutique winery, making less than 5,000 cases a year, and located in a still relatively obscure wine region, what are the greatest challenges your face in promoting your wines?

We are largely a direct sales winery, and are not looking for a distributor; we do work with a coupe of brokers, but in today’s tough wholesale environment, their contribution to the winery’s bottom line has become rather insignificant. Most of our wines are sold directly across the counter in the tasting room, or to our wine club, which has currently about 1,000 members, and to whom we ship two wines each quarter. Overall, our clientele is not a highly sophisticated one - in a wine sense, anyway - so, in order to have wines for palates ranging from first-time tasters all the way to really sophisticated tasters, and to meet the needs of the wine club, we produce a wide range of wines, although almost all are single varietal, and most are totally dry (we concede the sweet wine market to our competitors). We see annually 25,000-30,000 tasters in a very small tasting room, so numerically we have plenty of visitors. The challenge is getting them to buy - hopefully, cases rather than individual bottles. Tasting before purchase helps, of course, and for credibility we enter our wines in selected wine competitions, primarily the half-dozen or so I judge each year, and we generally do quite well. We also never pass up a chance to host visiting wine writers or any other opportunity for free publicity; we’re too small to have our own PR program, but our Temecula Valley Winegrowers Association works with a PR firm, and we cooperate enthusiastically with them. We also do occasional off-premise tastings and winemaker dinners.

What prompted you to pursue winemaking as a career? If not winemaking, what path would you have chosen?

Passion for wine was the driving motivation; I never expected to get rich, but did hope to be able to make a living at winemaking, and by and large, that’s how it has worked out. But it was good to have Nancy’s salary as a kindergarten teacher! I majored in Political Science with an emphasis in international relations as an undergraduate student at San Diego State, with vague ambitions to join the Foreign Service. However, I’m one of those people with a genius IQ but a mediocre academic record, not exactly what the Foreign Service is looking for. After graduation I was drafted into the Army, and during my time there, at my cushy desk job with relatively little to do, I had plenty of time to ponder my future; teaching seemed a reasonable option, so after my Army discharge I returned to San Diego State as a grad student, and spent two years completing a General Secondary teaching credential, using accrued educational benefits from my brief military career. If not for indulging my passion for wine, I likely would have remained in the classroom.

Describe your winemaking philosophy.

Our philosophy as a Temecula winery is to produce and sell wine only from Temecula and/or South Coast-grown grapes from grape varieties that have proven to do well here in our soils climate, and micro-climates. We are open to trying new varieties - and have pioneered several - within the limited confines of our ten-acre vineyard, and have worked with growers willing to take a chance on varieties untried in our region, but which show promise for our growing conditions. As winemakers we’re not highly experimental, but are not averse to trying new winemaking products and techniques. We do fining and filtration, believing that, in the long run, these techniques produce more stable, long-lived wines, with no detriment to perceived quality. We buy high-end barrels, both European and American, maintain them well, and dispose of them after several uses. We fall somewhere on the spectrum between “leave the wine alone and let nature take its course” and the highly interventionist school.

What wine varieties would you like to see the public embrace more fully?

Well, naturally, I want the public to embrace the wines we can do so well here, what I call the Mediterranean varieties. Since we are, as a region, largely dependent on direct sales, these are easier to sell, because the customer can taste the wine before buying.

Much has been written and debated concerning the 100 point rating scale. Some say it has empowered consumers, others claim it has distorted wine prices, while still others say it has actually changed the quality of wines being produced. What do you see as being the long term impact of the 100 point rating system?

I wouldn’t mind seeing the 100-point scale go away, especially since so many wines rated on that scale are the product of a single evaluator. It’s true that wines have become dramatically better (I’ve been judging wine for 30 years, and in the early years it was common to give medals to 20-30% of the entries, whereas today it’s more like 60-70%. The judges have not become lax; the wines have just gotten much better!); I just don’t believe the 100-point scale should be given credit for the improvement. I would attribute the improvement to market forces, foreign competition, better winemaking, and better winemaking equipment, products and techniques. I don’t know what the future of the 100-point scale might be; I guess the scale has replaced the knowledgeable guy you might have found in the small, neighborhood wine shop, now largely extinct and replaced by mega wine stores. As far as impacting prices, again, I wouldn’t credit - or blame - the 100-point scale; those ultra-high prices are mostly for the so-called cult wines, a tiny segment, in cases produced, of the overall wine market.

It’s been long day at Hart Winery; you’re tired and sore. You finally get home: What is your beverage of choice and why?

Probably a glass of chilled, dry, well-made Sauvignon Blanc (I know, I’m probably supposed to say beer - my choice would probably be Bohemia from Mexico or Sierra Nevada Pale Ale). Lacking a good Sauvignon Blanc, maybe San Pellegrino water over crushed ice!