In Part I of this series, Wines of Burgundy's Beaujolais Wine Region: Quality You Might Not Expect, I discussed the history of Beaujolais and Beaujolais Nouveau wines. In Part II, I will continue that discussion, but more importantly, review the individual terroir and the producers of some very fine age worthy wines.

Almost all wine made in Beaujolais is made from the Gamay grape. This grape gets its name from the name of a hamlet in Burgundy near Puligny-Montrachet. It is a very old cross strain of Pinot Noir and Gouais, a white variety long ago grown in central Europe. Although other wine regions of the world grow the Gamay grape, perhaps nowhere does it do as well as the granite soils of Beaujolais.

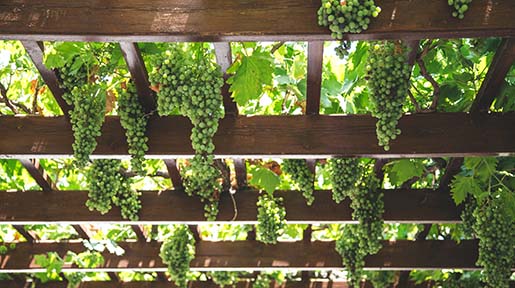

The Beaujolais region is unique in many ways. It has some the highest density plantings of grapes anywhere with 3,500 to 5,500 vines per acre. Many of the vines are trained in a traditional style called the goblet begun during Roman times. The Goblet method trains the branches of the vines upward into a circle. Whole clusters are picked by those wineries that use the traditional carbonic maceration fermentation. They can do this because most of Beaujolais is still harvested by hand and not machine. Machines would break the grapes. Harvest usually occurs in September.

As in Burgundy, there is a hierarchy to the wines of Beaujolais. At the basic end are the wines labeled as Beaujolais. About one half of all Beaujolais is sold under this AOC. These wines include the Nouveau wines. They are generally simple wines and are meant to be drunk within the first year of the vintage. More often they come from the southern part of the region where the soil is clay and limestone and not granite. By AOC laws these wines must have at least 9% alcohol. If the grapes can achieve a 10% or higher level of alcohol (either naturally or thru the addition of sugar at the winery, a process called chaptalization) they may also be labeled as Beaujolais Superiore.

The next step up in quality are the Beaujolais Villages wines. These must be made near one of 39 listed villages in the region. Villages wines can be very good wines and the best can improve in a cellar for a few years. If the grapes come from a single village, the name of that village may appear on the label, but it is not required.

The real stars and main reason for writing this article, are the Cru Beaujolais. This is the highest category of Beaujolais wines and indicates the wines come from one of ten designated areas. The word Cru refers to the entire sub-region and not a particular vineyard. More often than not, these wines will not even list Beaujolais on the label instead relying on the consumer to recognize the name of the Cru.

Each Cru has its own distinct personality. While some may be better than others, it is a combination of producer and style that should dictate what wines a consumer will purchase. The ten Crus from north to south are as follows:

Juliénas (near a village named after Julius Caesar) is at the northern end of Beaujolais The wines that have lovely floral notes with a bit of spiciness. These wines can age very well.

Saint-Amour lies just to the east of Juliénas. The wines have peach aromas in addition to the typical cherries and currants. Its wines are medium bodied and in need of a few years in the cellar before consuming.

Chénas is the smallest of the Crus. It lies south of both Juliénas and Chénas. The wines have a beautiful floral bouquet. The better wines from here can easily last ten years.

Moulin-à-Vent, sometimes called the king of Beaujolais wines for its masculinity, was carved out of the southern end Chénas because the wines were of a much more intense quality. The soil contains manganese which causes the vines to have exceptionally low yields resulting in more concentrated wines. These are sturdy wines that can age well for ten years or more.

Fleurie is to the southwest of Moulin-à-Vent. It is perhaps the most famous of the Cru wines. A feminine wine, it is sometimes referred to as the queen of Beaujolais wines. The wines from here have a great texture and are perhaps the quintessential Beaujolais Cru. They really need a few years from vintage to really show their goods and in a great vintage can improve for 10 years and drink for 10 more after that.

Chiroubles is southwest of Fleurie. The wines there somewhat lighter bodied, delicate wines that have almost a new world Pinot Noir quality to them, even in their youth. These gain a lovely complexity with a couple of years in the cellar.

Morgon is east of Chiroubles, and just south of Fleurie. These wines may be the best wines of all the Crus. With age they take on a Burgundian like quality and complexity.

Régnié is southwest of Fleurie. It is also a lighter bodied Cru. This is the newest of the Crus (having been elevated from Villages status in 1988). I like to think of these wines as being more feminine. To me, they are quite Grenache-like and will improve for a few years in the cellar.

Brouilly is directly south of Fleurie. It is the largest of the Crus. They are some of the lightest Cru wines with lovely aromatics. Typically these do not age as well as others. This is the only Cru that allows (up to 15%) of other grapes added to the wine.

Côte de Brouilly is a subsection of Brouilly but is its own Cru. These are at the top of the slopes while the Brouilly are at the bottom. The wines are more robust than the Brouilly wines, often with more concentration and more intense fruit.

Most of the better Cru winemakers have adopted more modern techniques in the cellar if not also in the field. Most now use regular fermentation and not carbonic maceration. Many also utilize some amount of oak too. Such wines are normally known as Cuvée Élevée en Fûts de Chêne. The use of oak is controversial in Beaujolais. If what you are looking for is the light, fruity wine meant to be drunk young, then perhaps the use of oak is disappointing. In a deft winemaker’s hand, the use of oak can round out a wine and help it age past those first few years.

As in all wine regions, the producer is more important than vintage or geographic designation. Any discussion of Beaujolais should really start with Georges Duboeuf. His name can be divisive among aficionados of Beaujolais. In my opinion, he makes some very nice Cru wines that tend to be fruit forward, accessible and inexpensive. He also is an expert marketer and his wines very popular. Some of the better Crus can age but I don’t recommend that with Dubouef wines as a general rule. In hotter years, I think he is very good at producing wines that accentuate his style and strengths. These are the wines to serve chilled at outdoor summer events.

If you are looking for very good Beaujolais, be sure to try some of the smaller producers as well. Perhaps the best place to start is with a group of producers called the Gang of Four. In the 1980’s, four producers in Morgon realized they needed to counteract the deteriorating reputation of Beaujolais. Sales remained good for Nouveau, but it was lowering the reputation of the region as a whole. Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Guy Breton and Jean-Paul Thévenet banded together fashioning quality wines that avoided the use of pesticides and were non-filtered. The resulting wines were splendid wines and achieved a degree of commercial success that allowed others to follow in their footsteps. The “Gang of Four” each continues to make wine and I would encourage everyone to try a bottle. They can be found for around $25 a bottle.

There are other producers who should not be missed. Coudert makes a wine called Clos de la Roilette in Fleurie that is excellent. The wine can be drunk on release but it really needs to be aged for a few years to see the full picture. In good vintages, it can be easily cellared for ten years or more. Jean Claude Lapalu is another excellent producer. His wine is a bit more modern in context and very good. He makes a very good village wine but look for his Brouilly Cru wines. They should be available for around $25 or less. Cheysson is a producer who makes a very good Chiroubles. The 2006 can still be found for around $20.

Finally I want to mention Pierre Chermette who makes wine under the Domaine Vissoux label as well as his own. In past vintages Vissoux took prominence on the label, but recently the Pierre Chermette name is more prominent. These are some of the best values in wine anywhere. He makes a variety of Cru wines including Fleurie (my favorite), Moulin-à-Vent, and Brouilly. They are very good wines that can be found for under $25. The wine to look for though, is the Cuveè Traditionell Vielles Vignes. This wine, now up to almost $20, has wonderful texture and complexity. It ages wonderfully turning from a fruit filled wine to one of complex earthiness. Chermette also bottles some youthful Beaujolais under his name alone. These are nice wines that should be drunk on release and not in the class of the Vissoux wines.

There are many more quality wines coming from the ten Beaujolais Crus. Nègociants like Louis Jadot, make some very good wines at that level. The top wines should not cost more than $25 and often less than $20. For your convenience, you may want to view the Beaujolais Wine Vintage Chart. Although not on the chart, the wines from 2007 I have had are quite promising. I would encourage you to try the Cru wines of Beaujolais. If you like them, perhaps think of laying a bottle or two down for a few years just for fun. I would love to hear about your experiences.

Loren Sonkin is an IntoWine.com Featured Contributor and the Founder/Winemaker at Sonkin Cellars.