In the winter, they stretch above the ground like old crows’ claws reaching for the sky. Amid the bright green of the groundcover and vivid yellows, reds and oranges of the flowering cover crops, one could easily mistake these black stumps for dead. But they are just dormant for now, mustering the energy to push out yet another year’s worth of fruit that will produce the liquid gold that old vine zinfandel can be.

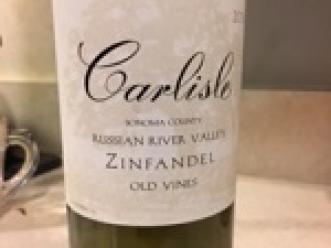

While there are no rules for how old vines must be to call them “old,” the finest old vine zinfandel vineyards are in the century range, planted in the late 1800s and early 1900s by Italian immigrants who had come to Sonoma County after the gold rush. In those days, lacking sophisticated trellising systems or irrigation, farmers simply plopped the vines in the ground in a grid pattern as their families had done in the mother country. Taking another trick out of the homeland bag, they interplanted whatever different vines they had on hand, a few petite sirah vines over here, a few carignane over there.

Luck or intuition followed those farmers a century ago, as they planted their vines on rootstock that would prove to be resistant to the many pests that came and went through the years, including several major phylloxera outbreaks (phylloxera is a tiny insect that feeds on the vine’s roots) that wiped out many local vineyards.

Those old vines have come back to life over the past month or so, nourished by the winter rains and the water table their old roots have long since tapped. With less rain this winter than most, the old vines promise to suffer greatly throughout the dry growing season, and by doing so, have the potential to produce wines of exceptional depth.

In their youth, these vines produced perhaps 4 or 5 tons per acre; in their old age, the vines will generously give up a ton and a half or 2 tons per acre. But what the vines have given up in productivity they have invested in intensity, and that’s what keeps farmers from pulling them out and replacing them with high density, expertly trellised, and ultimately higher yielding new vines. No, these vineyards are still greatly prized by wineries because science has yet to replicate the quality and intensity of the fruit they bear.

During the summer, growers will make a few passes through the vineyards to thin back the crop. As the old vines begin to make their final march to harvest, growers will make another pass to cut back leaves and shoots to expose the fruit to the sun. Then at harvest, the whole field will be picked at once (by hand, of course), the petite sirah tossed in with the carignane and zinfandel.

Barring a disaster like heavy fall rains, 2007 promises to produce some incredible old vine zinfandels from Sonoma County.