Our first visit to Chateauneuf-du-Pape, the summer home of the popes in the fourteenth century, was on a gray December day. We had just driven up from Nice for a visit to the vineyard areas of the southern Rhone Valley. We were hungry and decided to have lunch in Chateauneuf because of its location just off the Autoroute. We planned to have lunch at La Mule des Papes in the middle of the village, but the menu looked too pedestrian so we looked around. We found a tiny place, La Garbure, just up the hill from the village square.

Naturally, we ordered a bottle of Chateauneuf-du-Pape with our lunch. La Garbure’s list included many producers of the local wine, several of which were not familiar to us. We tried a bottle from Pierre Usseglio. In the mouth, it tasted warm, if there can be such a thing, and that isn’t a reference either to the actual temperature or the alcohol, but rather to the flavor profile. On our cold winter day, it was as if we had opened a bottle of summer sunshine. As a good Chateauneuf should be, it was delicious, rich and full-bodied. Needless to say, we greatly enjoyed our introduction to the wine of Pierre Usseglio, who is regarded as a good but not outstanding producer of Chateauneuf-du-Pape. By the way, we also greatly enjoyed the Provençal menu at La Garbure, and we have returned there often since then.

The Chateauneuf-du-Pape from Pierre Usseglio was notably different than the Chateauneuf with which we were most familiar, that of Chateau Beaucastel, or some of our other favorites, such as Domaine du Vieux-Telegraphe. But despite those differences, they were all far better than some mediocre wines we have encountered from this appellation.

After our lunch, we began driving the back roads through the vineyards of this famous appellation. We had read about and seen pictures of the very stony vineyards of Chateauneuf-du-Pape. But we soon observed that some of the vineyards had few such stones, other vineyards had smaller stones and some other vineyards were covered with the expected large stones. Clearly, not all Chateauneuf-du-Pape vineyards were the same in this respect.

We also noticed that the appellation has gentle hills, that some vineyards sites were higher than others, and that some vineyards were on slopes while others were virtually flat. Just what did these vineyards and the wines from them all have in common, except a name?

Here we were in the birthplace of the French appellation controlée system and in the most famous appellation in the southern Rhone Valley, yet there seemed to be as many differences as similarities. We looked further into this matter as we tasted, and we found a lot of reasons for the wide variety of wines coming from this single appellation.

Varietal differences

Chateauneuf-du-Pape is famous for allowing its red wines to be made from up to 13 different grape varietals (actually 14 if Grenache Noir and Grenache Blanc are counted separately, as they should be). Grenache Noir is the principal red varietal, and is supplemented by other red varietals (Mourvedre, Syrah, Counoise, Cinsault, Vaccarese, Terret Noir, Muscardin and Picpoul Noir) and white varietals (Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Roussanne, Picpoul Gris and Picardin). The use of the combination of red varietals adds structure to the predominant Grenache and complexity to the flavors and aromatics. The white varietals increase the freshness, flavor complexity and aromatic nuances. The red wine is concentrated and deeply colored, so the addition of small proportions of white doesn’t dilute its appearance.

But not all Chateauneuf-du-Pape reds have the same blend of varietals. Far from it! A major factor accounting for the wide diversity among the wines are the vastly different blends used by different producers. At one end of the spectrum, the outstanding producer Chateau Rayas uses nearly all Grenache Noir. At the other end of the spectrum, the outstanding producer Chateau Beaucastel uses all the permitted varietals, limits Grenache Noir to only about 30%, and uses an uncommonly high proportion of Mourvedre (also about 30%). Needless to say, Beaucastel makes a very different wine than Rayas. Beaucastel even makes a limited bottling (Hommage a Jacques Perrin) that is about 70% Mourvedre and has only about 10% Grenache. Syrah, the red grape of the northern Rhone Valley, is typically used in small proportions in Chateauneuf-du-Pape and elsewhere in the southern Rhone Valley. But Chateau Fortia has made a Chateauneuf (Cuvee du Baron) with about 45% Syrah, and uses up to about 30% Syrah in its normal bottling (Cuvee Tradition). The wide range of different blends partially accounts for the wide range of wines produced within this single appellation.

Vineyard, geology and soil differences

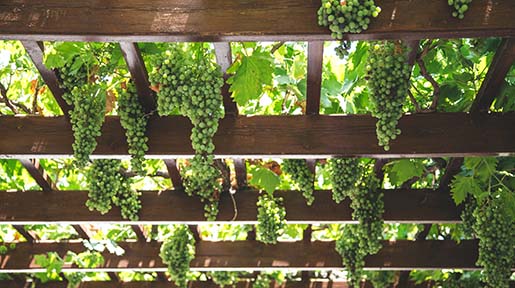

The vineyards of the appellation extend over about 8,100 acres in parts of the Communes of Orange, Courthezon, Bedarrides and Sorges in addition to Chateauneuf-du-Pape itself. The summers are hot and the Mistral, the famous Provençal wind, blows about 1/3 of the year, drying the grapes after summer storms and preventing pests and diseases. Most of the vines are head pruned and resemble old vine Zinfandel in California. The majority of the vineyards have very old vines, readily evidenced by the gnarled trunks. Appellation rules permit only hand harvesting.

The soils in many of the vineyards are organically poor. Only plants such as lavender and thyme that don’t need rich soil thrived before the vineyards were planted. The grape vines struggle and grow deep roots in these soils.

The higher vineyards are covered with the famous smooth, rounded quartzite cobblestones, called galets or galets roulés, the size of grapefruit or even footballs. These are most common north of the village. South of the village the soil is gravelly and east of the village the soil is sandy. In some areas, the galets are small pebbles. These surface differences have varying heat retention properties. The large galets hold the hot summer sun and release it slowly after sundown. The developing grapes on the low vines absorb this radiating heat.

The areas without the large galets don’t retain as much heat. But many experts dispute that the galets are a determinant of quality, pointing out that the Chateauneuf vineyards all receive plenty of heat and that very high quality wines are also made from the less stony vineyard sites. Just as Beaucastel and Rayas are polar opposites with respect to varietals, so too they are opposites with respect to the stones (Beaucastel’s vineyards are covered with the galets roulés, whereas Rayas’ vineyard has none).

Deeper down, the subsoils are layers of clay, sand and pebbles. The areas with more clay in the subsoil retain more water than the sandier areas. The wines reflect these differences. Richer wines are produced where the subsoil has more water-retentive clay and slightly lighter wines are produced where the subsoil has a higher proportion of sand.

Many Chateauneuf wines come from a single vineyard. Examples are Chateau Beaucastel and Chateau Rayas. Many others are from blends of several vineyard sites, often in different areas of the appellation. At the extreme, Domaine Mathieu has about 45 separate vineyard parcels from throughout the appellation.

Planting and growing practices are yet another variable that directly affect the final outcome. As is true elsewhere, Grenache yields must be kept down to produce outstanding wine. In the hot southern Rhone, Syrah needs to be planted in the cooler microclimates. Mourvedre prefers to be planted in sheltered, south-facing sites with water-retentive subsoils.

Diversity of growers, producers and styles

Over 300 growers tend the vineyards. Of these, between 225 and 250 bottle part or all of their own production. The quality among these different producers varies widely, from outstanding to only passable or worse. Increased popularity of Chateauneuf-du-Pape in the international markets in recent decades has lead to increased prices, which in turn has contributed to generally better wine-making and higher quality. Nevertheless, plenty of indifferent wines are still produced.

Chateauneuf-du-Pape producers offer a wide range of styles.

The traditional style, like the Pierre Usseglio we enjoyed at lunch that winter day, is predominately (about 2/3 or more) Grenache with some (10-15%) Mourvedre and Syrah and a small proportion of the other permitted varietals. Typically, the grapes are not destemmed and the wine is aged in large wood foudres, not small oak barrels, so the effect of the oak is tempered. Generally these producers fine and filter only lightly, if at all, leaving the full-bodied texture in the wine. These wines tend to be concentrated, ripe and age-worthy. Les Cailloux and Le Vieux Donjon are some outstanding examples of this style.

Many producers are now making their wines for early drinking, often by destemming and using carbonic maceration for all or part of the grapes to accentuate the fruity character. These producers are more likely to fine and filter the wine, resulting in a lighter wine with less typical Chateauneuf-du-Pape character and with less complex flavors and aromatics. Many of the negotiant-produced wines are in this category. This isn’t a style we favor in most cases. For those who do enjoy this style, a good example is Domaine de Nalys.

There are a few producers whose wines are grounded in the traditional approaches but who have their own unique voices. The prime example is Chateau Beaucastel, which uses a high proportion of Mourvedre as well as a little of all the permitted varietals in its blend. Beaucastel also favors more Counoise than most other producers. As a result, its wine is distinctive. Les Cailloux and Chateau de La Nerthe are other producers who have been increasing the proportion of Mourvedre in their blends.

While Chateauneuf-du-Pape has many outstanding producers whose wines justify the fame of the appellation, sadly there are also many inferior producers. Some don’t take the proper care in the vineyard, such as allowing the Grenache to bear too much fruit. But more often the problems are in the wine-making. We have tasted too many weak, oxidized examples. Some producers still bottle as they sell, causing great variation in the wines of a single vintage.

What is the identity of Chateauneuf-du-Pape?

On one hand, Chateauneuf-du-Pape is one of the great wines of the world. On the other hand, a significant proportion of the wine from this famous appellation is far below the standard of the best producers. And even among the best wines of the appellation, there is tremendous variation due to many factors, including different varietals in the blends, different vineyard sites and different wine-making philosophies. It is hard to think of any other French appellation that encompasses such diversity of both quality and style. There is no single identity to the wines of Chateauneuf-du-Pape.

A wine lover tasting Chateauneuf-du-Pape needs to take these differences into account and to remember which wines were highly enjoyable and why, and which wines failed to impress. Those observations will facilitate finding some personal favorites and discovering which style and producers are preferred.

As a starting point, here are some of our favorite Chateauneuf-du-Pape producers (and they are all very different): Chateau Beaucastel, Les Cailloux, Clos des Papes, Domaine de la Mordoree, Domaine Roger Sabon and Domaine du Vieux-Telegraphe.