I step out of the “working van,” as our tasting guide, Nathalie Müller, parks next to rows and rows of grapevines. My husband and friends clamber down and inhale the clean air. High above the town of Leimen, I can see the grapevines stretching across the hills. Ms. Müller grabs a plastic crate of wine bottles and offers us each a wine glass. Deftly, she opens a bottle and pours 2006 Leimener Kreuzweg Auxerrois dry Kabinett into our glasses.

It’s Halloween, and I’m lucky enough to be in Germany during the last weeks of the wine harvest. Our friend, Mark, who lives in Leimen, has arranged a wine tour for us. We’re in the Badische Bergstrasse, part of the Baden wine region, which is Germany’s southernmost wine growing area. Ms. Müller tells us that we’ll understand and appreciate the wines more if we drink them where the grapes were grown. As I hold my glass up to the sunlight, I’m already convinced she’s right.

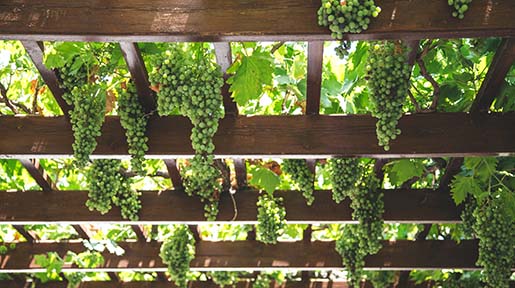

This is a wine tasting like no other I’ve experienced. The Müller family has owned and operated Weingut Adam Müller for 272 years – that’s nine generations, so far. Ms. Müller studied oenology at Germany’s famous Geisenheim Research Center, as did her husband, Matthias Müller. As she leads us up a wooden ladder to the next terrace of vines, Ms. Müller describes how much she loves this particular vineyard. She pours a 2006 Leimener Herrenberg, a dry grauer burgunder Spätlese (pinot gris), and tells us about this year’s weather and harvest.

In Germany, 2007 is being described as a “fairy tale” year, the kind of growing year that is perfect in every respect. Ms. Müller tells us that the first grapes picked this year in the family vineyards had a must weight of 85 Oechsle degrees, while the spätburgunder (pinot noir) grapes picked in the last weeks of October had a must weight of 103 to 104 Oechsle degrees. Her eyes shine as she describes the year’s growing conditions and optimal weather. Clearly, Ms. Müller is passionate about every aspect of her profession.

We next try what Ms. Müller describes as her “book wine.” This is the wine she enjoys drinking while reading a good book on a quiet evening. This wine turns out to be a 2005 Leimener Kreuzweg Muscat-Ottonel Spätlese. Unlike many muscats I’ve tried, this one isn’t overly sweet. It is, indeed, a wine to be savored.

Ms. Müller shows us the spätburgunder vines and explains how they are pruned back after the harvest. Nearly all the branches are cut away, leaving only one strong branch to support next year’s vines. The winery employs three people to work the vineyards throughout the year, and hires four extra people during harvest season and in January. Ms. Müller pours a shimmering, dry spätburgunder Spätlese that was grown across the river from Heidelberg Castle. I hold my glass up to the sun and twirl it slowly, watching the wine trace red paths along the bowl.

German wineries have met new challenges as European borders and EU import regulations have changed. Many winemakers, including the Müllers, further refined the German emphasis on excellence and worked to limit harvests to improve the quality of the grapes. “The younger generation has to look to quality,” Ms. Müller says.

She takes us to an area planted with young vines. For the first three years, no grapes are harvested from these plantings, as grapes weaken the vines before they have a chance to establish themselves. The first pressing from these grapevines, called Jungfernwein, is a very special vintage that celebrates the maturation of the vines.

My husband asks about insects and other pests. Insects are less of a problem, we learn, because the Müllers grow grass and other low plants between the rows of vines. This encourages beneficial insects to come to the vineyard. These friendly visitors keep the insect pests under control.

Birds are another story. Ms. Müller tells us that the birds ignore blinking lights, which some wine growers use, and that recorded calls from birds of prey are more effective in keeping birds away from the grapes than any other method the Müllers have tried. Nevertheless, birds are always a problem, especially during the days leading up to the harvest. “They only like the ripest grapes,” Ms. Müller tells us.

In some of the Müllers’ vineyards across the Neckar River from Heidelberg Castle, old compact discs are tied to the rows of grapevines. The CD’s spin in the wind and flash in the sunlight, discouraging local wild pigs from munching on the grapes.

As we admire our last glass of wine – a garnet-colored, dry Lemberger spätlese – we greet a group of hikers strolling through the vineyard. The Müller family maintains its tradition of allowing walkers and hikers to pass through the vineyards, preferring to keep the pathways open for the enjoyment of local residents. Occasionally, Ms. Müller says, discourteous visitors cause problems, but most are polite and respect the vines and the property.

I know I’ll never find an Adam Müller wine in the United States. Ms. Müller tells us that it’s very difficult for a small winery to comply with American import requirements. Many German wineries sell most of their wines locally and within the EU, and consider these markets more than enough. The pinot sekt we taste at the Müllers’ showroom is no longer available; it sold out in four weeks after it was profiled as a New Year’s Eve sparkling wine selection in a local magazine.

Weingut Adam Müller has picked up several awards this year, and the wine competitions are still under way. Adam Müller wines have received gold and silver medals from MUNDUSvini, Germany’s worldwide wine competition, and from the Badischer Weinbauverband (Baden’s Viticulture Association).

The only German wine to make Prinz Münchner magazine’s Top Five for 2006 is Adam Müller’s Leimener Kreuzweg Auxerrois Kabinett trocken (dry). The article, “Who has the Best Wine in Munich?” rates this wine as one of Munich’s five best white wines for taste and value.

We pack up the glasses, bottles and crate and head back to the van. Ms. Müller stops to pick up her young son en route. As we drive back to the wine shop, he tells us about school and about his younger sister. It’s clear that Generation #10 is already quite comfortable in the family business offices.

This has been a day to remember. Ms. Müller’s intimate involvement with the family winemaking tradition, combined with her extensive understanding of the art and science of winemaking, gave me a fresh appreciation of German wine. She knows about the soil, the microclimate and the hours of sunlight unique to each vineyard, and she shares her knowledge freely, stating, “There are no secrets.”

The real secret, I am convinced, is a passion for winemaking. From bare earth to finished product, every aspect of the winemaker’s art is enhanced by the winemakers’ knowledge and enthusiasm. Today, I’ve had a chance to see it all first hand, and it’s been a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.