“It’s difficult to export wine because we drink a lot” is the response I got when asking why Swiss wine does not exist on the international market.

Switzerland, a tiny independent country in the heart of Europe with a population of 7.5 million, is divided further by languages; French, Italian, German, and Romanche. While each region is actively involved in wine production, the most action occurs in the French part, specifically in the cantons Neuchatel, Geneva, Vaud and Valais. Lakes and rivers play a large role in regulating the effects of the Alps. Most of these vineyards grow on steep south

In Valais alone (which is the most productive canton, accounting for over 40% of Swiss wines) there are 49 varieties under the AOC Valais label. Still the most prevalent varieties are Pinot Noir, Chasselas, and Gamay. There is also a rising interest in local grapes (Cornalin, Petit Arvine and Humagne Rouge) and to varieties that are well suited for the Valais

Wines are largely sold under the name of the varietal, along with the trade name of the producer and the AOC designation. However because of attachments between vines and their locations, some titles include the grape alongside the place of production. For example: Fendant at Sion, Chardonnay at Conthey, Amigne at Vetroz, and Johannisberg at Chamoson.

Quite similar to Burgundy, the area is more of a patchwork quilt as it’s divided between 22,000 owners, often passed down within families from one generation to the next. Then again it’s important to note that only about 250 of these fragmented properties are more than two hectares in size, the rest really remaining to be fragments.

There are so many fascinating and wonderful grape varietals in Switzerland, some of which are found nowhere else in the world.

Chasselas

Locally known as Fendant, this is the white wine of Switzerland. It is a dry, acidic and clean-tasting wine, with an extremely floral nose and a fresh, even sparkling, attack in the mouth. Fendant is the perfect accompaniment to the local Swiss cuisine; rich cheese fondue, raclette, and cold meat dishes.

Petite Arvine

Particular to the Valais region this wine is rare but amazingly distinct. It has a vivacious nose of grapefruit and rhubarb, in the mouth it is complex and round, with a characteristic hint of salt on the finish.

Gamaret

A new grape variety created about thirty years ago by crossing Gamay and Reichensteiner grapes. It is vivid violet ink in color, smells of jammy fruits and smoked prunes and has an interesting complex taste.

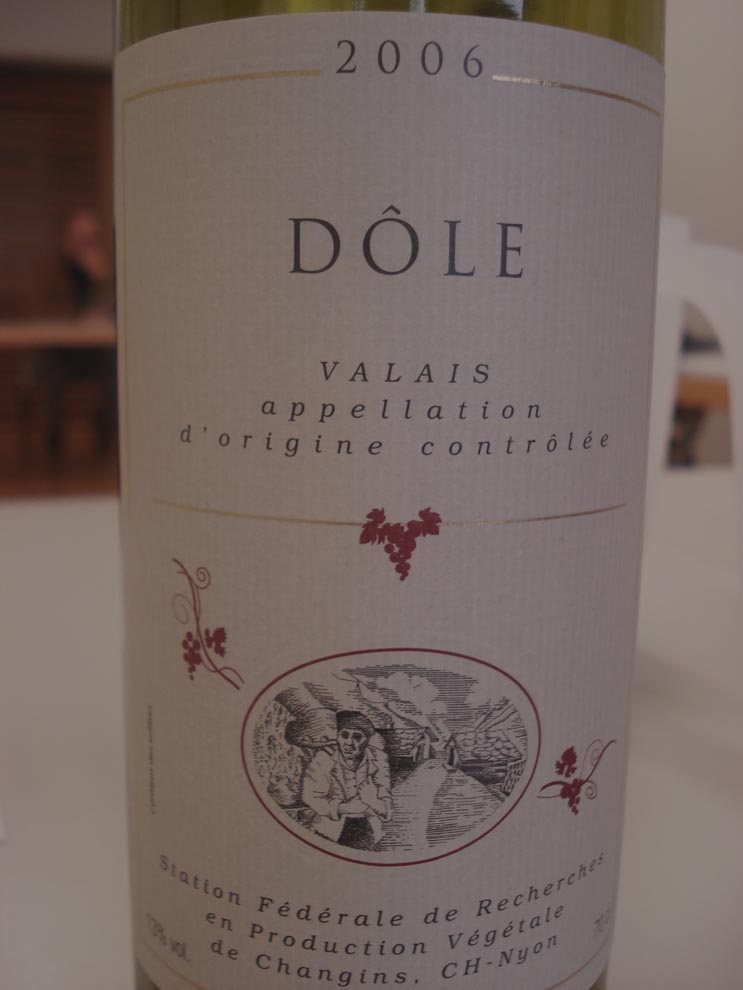

Dôle

This is

Cornalin

Switzerland’s more muscular red wine, aged in oak and typically eaten with game. The aromas are deep and powerful, sometimes smoky with essence of animal. However it is not so aggressive in the mouth, in fact, while the taste remains masculine, Cornalin is often balanced, velvety and smooth.

Now back to my question as to why no one knows about Swiss wine. In reality about less than 2% of Swiss wine is exported and it doesn’t travel too far as its prime markets are neighbouring Belgium and Germany. But the reason is more to do with quantity than quality. Small vineyards on difficult terrain result in low production levels among individual winemakers. Often there is barely enough to supply the local market and its not uncommon for loyal Swiss customers to drive directly to the wineries and demand to buy whatever is available. So it really is difficult to export wine when most of it is absorbed by the Swiss people themselves. Tourism is another sponge on the Swiss wine supply and it remains to be the only way to discover this magnificent yet closed world of wine.