Dramatic. Historic. Traditional. Cutting-edge. All of these terms describe Germany’s Mosel-Saar-Ruwer wine region, often called “Moselle” in English-language guidebooks. Mosel wines are uniquely German and internationally acclaimed. Perhaps more than any other German wines, Mosel wines truly reflect their terroirs.

The heart of the wine region is the winding Mosel River. Two tributaries, the Saar and Ruwer Rivers, flow into the Mosel near Trier, Germany’s oldest city. The Mosel twists and turns as it flows toward Koblenz, where it meets the Rhine at the German Corner (“Deutsches Eck”). All along the river, vineyards plunge dramatically, almost unbelievably, toward the banks.

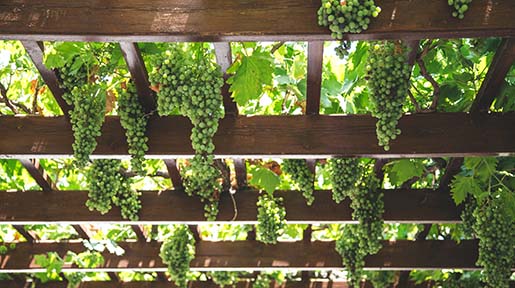

The steeply-sloped vineyards of the Mosel-Saar-Ruwer wine region are so difficult to work that the obvious question doesn’t even need to be asked. Of course, it’s worth it. No one would scramble up and down these hillsides, hand-harvesting grapes, if the resulting wines were mediocre.

In fact, Mosel winemakers will tell you that the steep slopes produce better grapes, since rainwater drains off quickly. Because the river winds back and forth on its way to the Rhine, the valley has many south-facing slopes, which have the best sun exposure. Given Germany’s latitude, every moment of sunshine counts.

Slopes, sunshine, and the region’s slaty and limestone-based soils combine to give Mosel winemakers the opportunity to make truly great wines, but the cost is high. German labor is expensive. The grapevines must be hand-tied to poles or circular forms to maximize the grapes’ exposure to the sun. Tending the vines requires hours of work, perched high above the river on dangerously steep hillsides. Workers even carry buckets of slate back up the hillsides to the vineyards after heavy rains. Some Mosel winemakers use machinery developed especially for their area, such as small monorail systems. Most work is done by hand, however, and the cost of planting, tending and harvesting Mosel’s wine grapes increases each year.

The result, however, is world-class wines. Sekt (sparkling white wine) and spätburgunder (pinot noir) are also produced in the Mosel, but top honors go to the region’s rieslings. Other white wine grapes, including weissburgunder and Müller-Thurgau, also grow well in the Mosel region. About 91 percent of the region’s vineyards are planted in white wine grapes; 58 percent are planted in riesling.

For many wine lovers around the world, “riesling” is synonymous with “Mosel-Saar-Ruwer.” This year’s “Ultimate Buying Guide,” published by Wine Spectator, awarded an astounding 99 points to two Mosel wines, while seven Mosel rieslings received 98 points. No wonder locals and visitors flock to the Mosel valley to visit wineries and taste the latest vintages.

If you plan to visit the Mosel region, head upriver from Trier to Bernkastel-Wehlen, where you can visit the winery of Markus Molitor. Molitor’s Riesling Trockenbeerenauslese Mosel-Saar-Ruwer Wehlener Klosterberg 2005 was awarded 99 points by Wine Spectator this year. You’ll need to call ahead to arrange your visit. (The winery’s website has English-language pages, which you can find if you click on the “English” tab at the top of the home page.)

Looking for lodging at a Mosel winery? S. A. Prüm offers not only award-winning wines but also a reasonably-priced guesthouse, where you can taste wines or simply enjoy the scenery.

If you do visit the Mosel, be sure to include the ancient city of Trier on your itinerary. You can see Roman ruins, including the famed Porta Nigra, or Black Gate, and Constantine’s Basilica. Trier’s cathedral also dates from Constantine’s time, which makes it Germany’s oldest church. Trier is packed with museums, monuments and trendy shopping areas. The area is perfect for walking or bicycle tours; the tourist information office can tell you where to rent bikes.

One unique way to taste the wines of the Mosel-Saar-Ruwer is to visit a “Straußwirtschaft,” which translates to “ostrich business,” but is in reality a seasonal wine bar and/or restaurant. Under German law, wineries can open temporary restaurants, as long as the total days of operation do not exceed four months in one year. To find a Straußwirtschaft, visit the Mosel between May and October and look for the Straußwirtschaft symbol, a straw wreath decorated with flowers and ribbons. You can also download the Straußwirtschaft-Pass, which has a listing of opening days, locations and even a “frequent buyer” card on the last page. If you visit eight different locations, you’ll receive a free bottle of wine at the eighth stop. The Pass is in German, but it’s fairly easy to understand, since it consists mostly of names, addresses and dates.

No matter when you visit the Mosel-Saar-Ruwer wine region, you’ll be rewarded with panoramic views, historic ruins and, of course, some of the world’s best wines.